Latest three-dimensional computer simulations are closing in on the solution of an decades-old problem: how do massive stars die in gigantic supernova explosions? Since the mid-1960s, astronomers thought that neutrinos, elementary particles that are radiated in huge numbers by the newly formed neutron star, could be the ones to energize the blast wave that disrupts the star. However, only now the power of modern supercomputers has made it possible to actually demonstrate the viability of this neutrino-driven mechanism.

Supernovae are among the brightest and most violent explosive events in the Universe. They are not only the birth sites of neutron stars and black holes; they also produce and disseminate heavy chemical elements up to iron and possibly even nuclear species heavier than iron, which could be forged during the explosion. Understanding the explosion mechanism of massive stars is therefore of fundamental importance to better define the role of supernovae in the cosmic cycle of matter.

Stars with more than about eight times the mass of our sun evolve by "burning" nuclear fuel to successively heavier chemical elements, thus converting hydrogen to helium, carbon, oxygen, sulfur and silicon, until a dense, degenerate core mostly made of iron builds up in the center. At this stage no further energy gain by nuclear fusion is possible, because neutrons and protons in iron nuclei possess the highest nuclear binding energies.

For more than 30 years there had been hope that ever more improved computer models would finally be able to demonstrate that this "core-bounce shock" is able to trigger a successful supernova explosion by reversing the infall of the outer stellar layers. However, the opposite turned out to be the case: Better models showed that the energy losses of the bounce shock are so dramatic that its outward propagation comes to a halt still well inside of the iron core. It became clear that something has to help reviving the stalled shock. Some mechanism has to supply the shock with fresh energy so that it reaccelerates and expels the stellar mantle and envelope in the supernova blast.

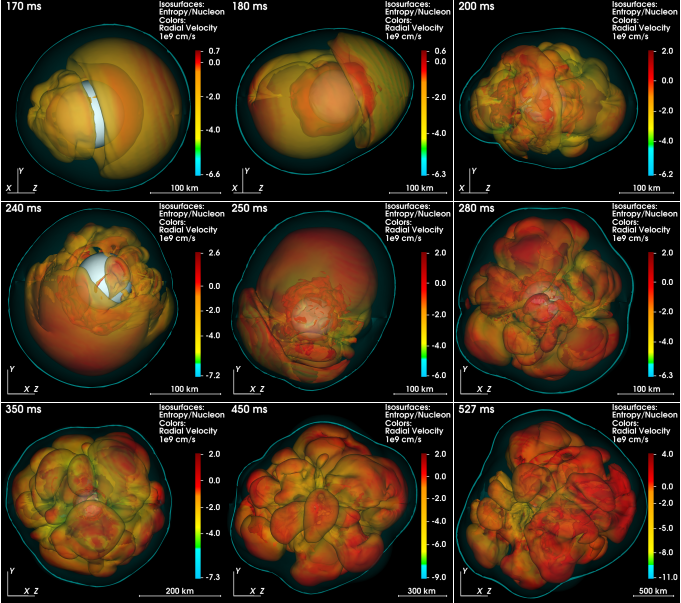

Fig. 1: Sequence of volume-rendering images that show the violent non-spherical mass motions that drive the evolution of the collapsing 20 solar-mass star towards the onset of a neutrino-powered explosion. The whitish central sphere indicates the newly formed neutron star, the enveloping bluish surface marks the supernova shock. (Visualization: Elena Erastova and Markus Rampp, Max Planck Computing and Data Facility (MPCDF)); copyright (2015) by American Astronomical Society).

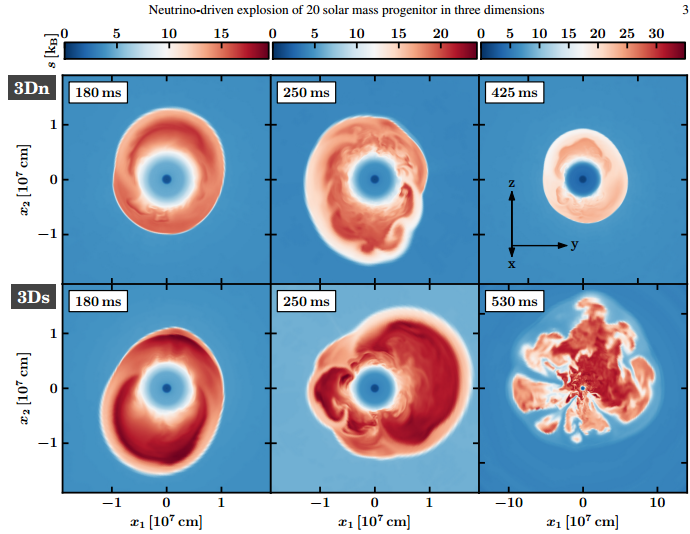

Fig. 2.— Cross-sectional entropy distributions (in kB per nucleon) for the 3D models without (3Dn; upper row) and with strangeness contributions (3Ds; bottom). The bottom row clearly shows stronger SASI activity in model 3Ds (180 ms, 250 ms), whose traces are still imprinted on the ejecta geometry after the onset of the explosion (530 ms; note the di erent scale).

Already in the 1960's it was speculated (in a seminal publication by Stirling Colgate and Richard White) that neutrinos might be involved. Myriads of these high-energy elementary particles are radiated by the extremely hot, newly formed neutron star. If less than one percent of them gets absorbed in the matter behind the stalled shock, a healthy supernova explosion will be the consequence (see  MPA research highlight 2001). This was shown, in principle, already in the mid 1980's with first sufficiently detailed numerical simulations by Jim Wilson and interpretative work by Wilson and Hans Bethe.

MPA research highlight 2001). This was shown, in principle, already in the mid 1980's with first sufficiently detailed numerical simulations by Jim Wilson and interpretative work by Wilson and Hans Bethe.

However, many aspects of the involved physics were still too crude and too approximate to be realistic. In particular, with the observation of Supernova 1987A it became clear that stellar explosions are highly asymmetric phenomena and non-spherical plasma flows must play an important role already at the very beginning of the explosion. Early multi-dimensional computer models ---mostly still in two dimensions, i.e., assuming rotational symmetry around a chosen axis for reasons of computational efficiency--- indeed showed that convection and non-radial mass motions provide crucial support to the neutrino-heating mechanism and enhance the energy deposition by neutrinos. Thus explosions could be obtained although spherical models did not find shock revival and did not lead to explosions (see  MPA press release 2009).

MPA press release 2009).

Nature, however, has three spatial dimensions and therefore these early successful models were critisized to be unrealistic and not reliable. In fact, not only the assumed axial symmetry is artificial, also the physics of turbulent flows differs in two dimensions compared to the 3D case.

Only very recently the increasing power of modern supercomputers has now made it possible to perform supernova simulations without artificial constraints of the symmetry. A new level of realism in such simulations is thus reached and brings us closer to the solution of a 50 year old problem.

The stellar collapse group at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (MPA) plays a leading role in the worldwide race for such models. With all relevant physics included, in particular using a highly complex treatment of neutrino transport and interactions, such computations are at the very limit of what is currently feasible on the biggest available computers. The model simulations are performed on 16,000 cores (equivalent to a similar number of the fastest existing PCs) in parallel, which is the largest share of SuperMUC at the Leibniz-Rechenzentrum (LRZ) in Garching (Fig. 1) and of MareNostrum at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC; Fig. 2) that the MPA team is granted access to. Nevertheless, one full supernova run, conducted over an evolution time of typically half a second, consumes up to 50 million core hours and takes more than 1/2 year of project time to be completed.

For a little more insight into the project see this:http://arxiv.org/pdf/1504.07631v2.pdf